Cutting Through The Noise: How to Interpret Medical Studies

"the only way to get published is to say something surprising" - John Ioannidis

Have you ever read a headline like “Coffee is good for our longevity” or “Chocolate helps you lose weight!” or “Red meat consumption leads to dementia” and thought… Wait, what?!

You're not alone. Nutrition research is all over the place—and that’s not just your perception. It is messy, and it can be manipulated to say whatever the researchers/scientists want it to say.

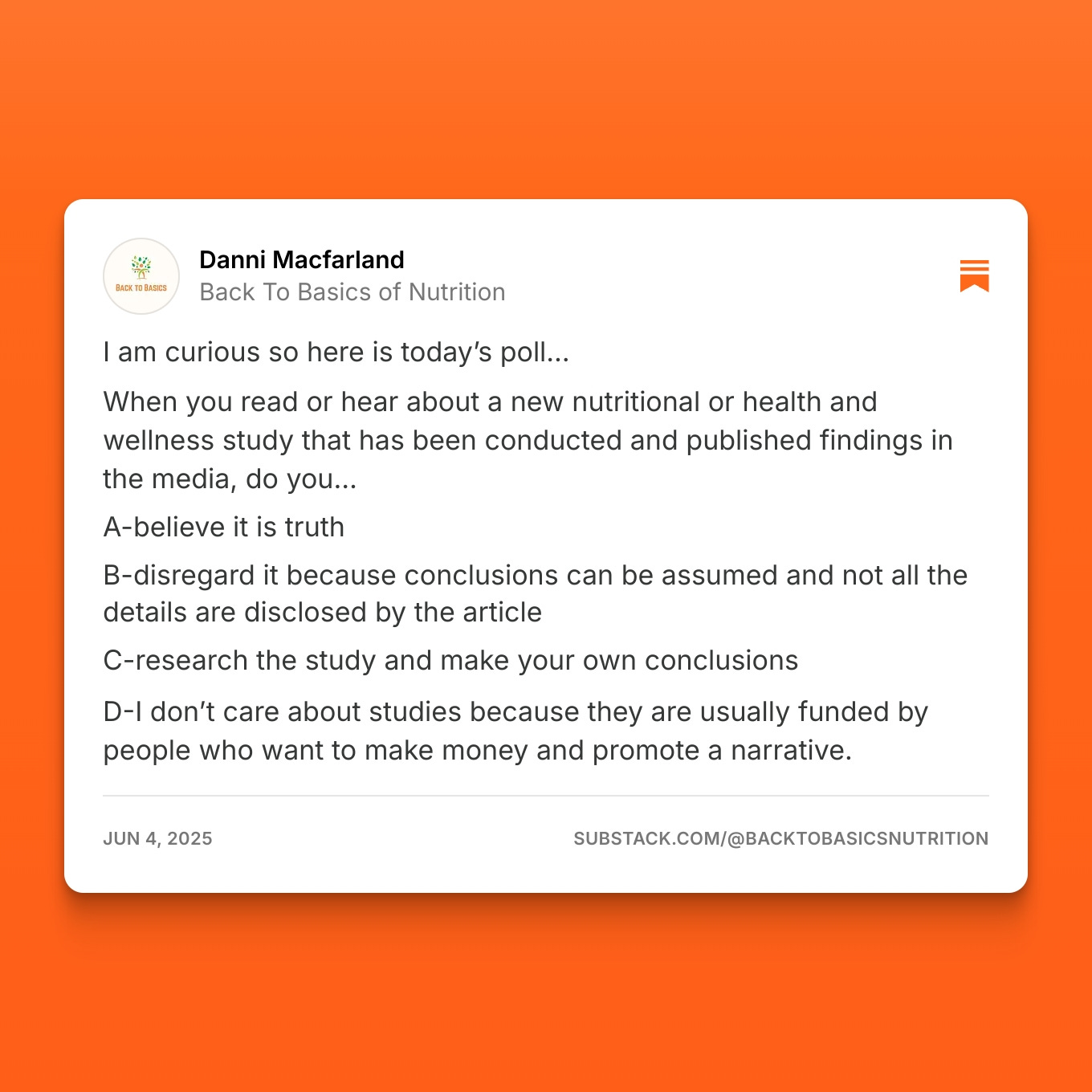

I posed a question to my followers in regards to scientific studies as I was genuinely curious as to who took what they read through the media and believed it or who took what they read and did their own research.

Maybe it was because my followers have my same mindset when it comes to health and doing research, but the replies I received were mostly C or D or both.

These medical scientific studies are done to prove a hypothesis. We all did experiments in high school chemistry class more than once. The goal is to pose a question and follow steps or actions to try to prove it. That is the same for studies on health and nutrition. But we only seem to hear about the ones that have a favorable outcome and prove the hypothesis researchers are questioning. There are studies that are done, that do not reach the outcome that was desired and surprising these studies are rarely published.

When studies are published most people do not do their due diligence and read the whole study to determine if what we are being told is true and if there are red flags to the study. Mainly this takes time, which most people do not have the extra time and honestly, most people don’t know what to look for in the studies.

When I see a study that might peak my interest, the first question I ask is - Who funded this study?, Why? and what was this study supposed to tell us.

First of all, all studies require funding. Money to pay the researchers and scientists to do the research. And let’s be honest here, who is going to fund a study and have the study provide negative outcomes for what they are researching. Most of the time it is studies are done for the benefit to make money.

For example, Coca-Cola is not funding a study on why drinking 12 cans of soda is bad for you. They would fund a study on how drinking soda is good for you or manipulate the data of the fore mentioned study to create a positive result.

Let’s be honest. Bias is real.

Medical Studies Are Messy

Medical and health research is messy and also can be manipulated to say whatever they want to conclude by playing with data. You don’t need a doctorate to read studies, you just need to understand how to spot the red flags and ask the right questions.

According to John Ioannidis a professor at Stanford University - ‘the incentive is to to publish papers, to get promotion and to get funding’. Ioannidis states that about 50% of all clinical reviews published are based on evidence that has been manipulated or is not relevant to the patients to whom the research is geared.

Doctors can pick and choose studies to substantiate their actions. There is most likely a study out there for medical any point of view. Cherry picking studies is done to support what doctors think is best for the patient and twisting the data to validate the treatment.

So here are some tools and questions to ask yourself to help you decipher those studies.

What type of study is it?

Randomized Controlled Trials (RCTs): Gold standard. Participants are randomly assigned to a test group or control group. Best for proving cause and effect.

Cohort Studies: Also knows as Observational or Epidemiology studies. Follows a group over time. Can show associations but not causation.

Meta-Analyses & Systematic Reviews: Summarize multiple studies. These can offer stronger conclusions—if the individual studies are high-quality.

Animal or Cell Studies: These can offer early clues but don’t apply directly to humans.

Most studies, especially in the health/nutrition realm are observational studies. Data is collected usually using surveys and questionnaires and researchers then look for common data points to point to a conclusion. These studies are proving correlation, not cause and effect and correlation does not always equal causation. Observational studies look backward and do not have a control group to adjust for variables.

For instance, there may be a study (and there is) that wants to prove people with high cholesterol have more heart attacks. While there may be a connection to that hypothesis, what other data was not taken into consideration. Do these people smoke, are the obese or do the lead a sedentary lifestyle or what other foods were prominent in the survey?

Look at the length of the Study

Many studies will terminate a study early because the intervention is working to well to justify continuing. This excludes any long term data that should be presented. Sure sometimes an intervention such as a drug will give you a quick fix, but continuing that treatment may negate the positive effects and also cause harm.

This was the case with the drug VIOXX, which was used as a pain medication for arthritis. In the short term, it relieved pain but long term used showed it caused heart attack, stroke and death.

Absolute Risk vs Relative Risk

Headlines love to say things like: “Eating bacon increases cancer risk by 20%!”

But here’s what they don’t tell you; if your lifetime risk of a certain cancer is 5%, a 20% increase brings it to… 6%.

Sounds a lot less scary, doesn’t it?

Selecting Participants

Some studies will start off on the wrong foot when it comes to participants. For instance, there may be a study that wants to determine if low estrogen in women contributes to dementia. When researchers selected participants, some of those women in the study were already dealing with dementia symptoms and that was not communicated in the conclusions. So the conclusion may be that yes, low estrogen does contribute to dementia and this selection process maximizes the outcome.

Wording Matters

When it comes to all those food studies, words matter. Distinguishing between ‘protein’, or what constitutes ‘processed meat’.

You don’t eat ‘protein’, you eat steak, or eggs, or lentils—each with unique nutrient profiles and effects.

Processed meats can mean anything from a steak to hot dog. Both processed in their own way.

Have a Critical Mind

Step One: Look to the bottom of a study (conflict of interest) to see who funded the study.

Then ask yourself: Is this conclusion supported by a body of evidence—or just one study?

If all else fails, go with human experience. Anecdotal evidence matters too.

And the biggest thing to remember is the uniqueness of every person.

Far too large a section of the treatment of disease is today controlled by the big manufacturing pharmacists, who have enslaved us in a plausible pseudo-science

-William Osler

If you found this helpful, hit the ❤️ button, leave a comment, or share it with a friend

Danni

The most misleading are the studies about processed meat, and the studies about high blood pressure. There are so many factors it’s impossible to control.